Reciprocal Tariffs and the High-Stakes Gamble Behind Them

/ 9 min read

Table of Contents

Stephen Miran’s Blueprint: A Guide to Restructuring Global Trade

In November 2024, Hudson Bay Capital senior strategist Dr. Stephen Miran, the current chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, published A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System,

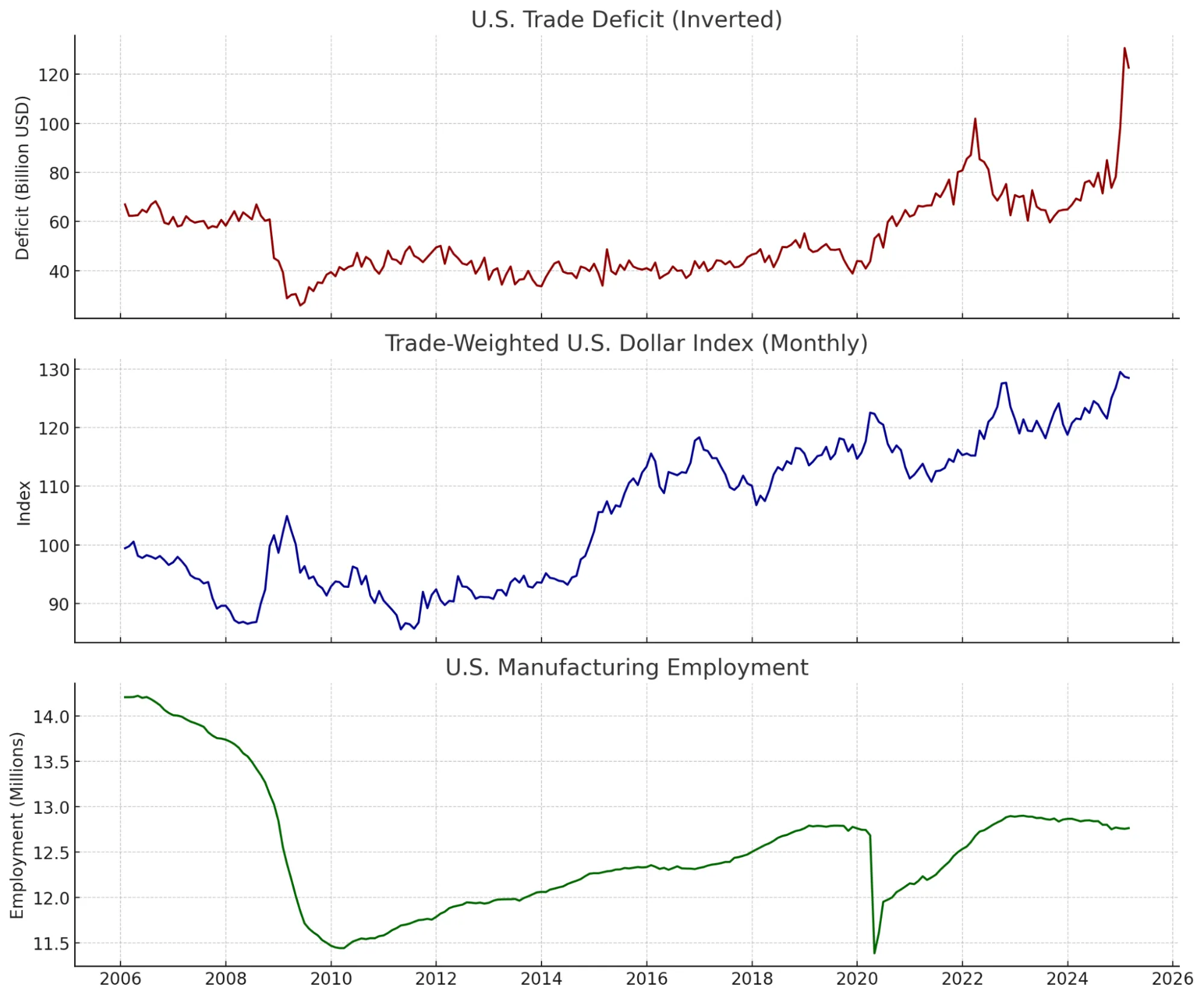

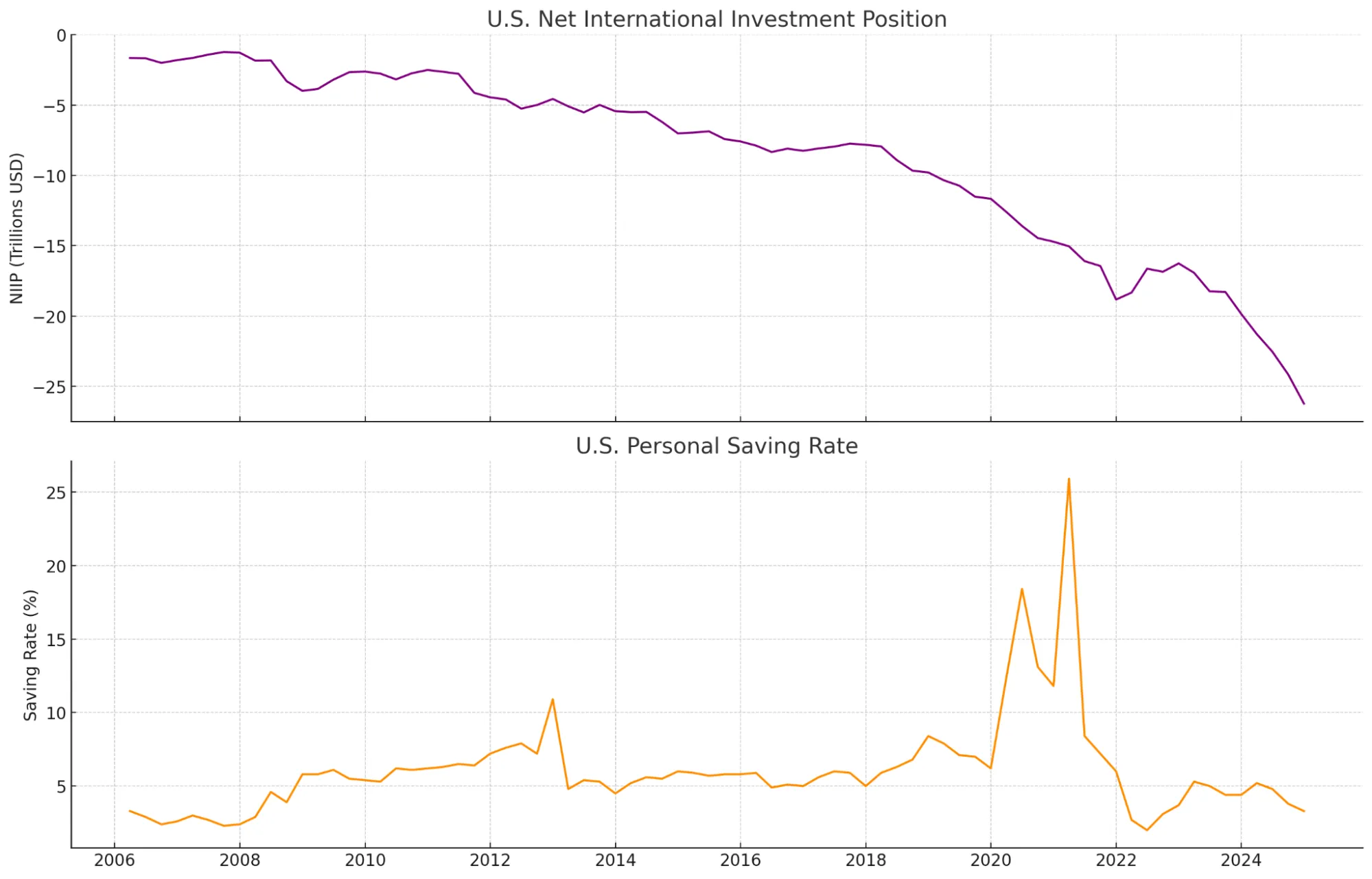

Miran’s argument builds on the well-known Triffin dilemma - the USD plays a unique role as the global reserve currency. Other countries hold U.S. dollars, mostly in the form of U.S. Treasuries, as part of their savings. When countries trade with each other, settlements are often made in USD. This creates demand for the dollar, supplied through deficits, which need to be balanced to retain trust in the currency. Inelastic demand continually strengthens the dollar, resulting in cheap imports and expensive exports. This widening trade imbalance has led to the erosion of domestic manufacturing, the hollowing out of the middle class, and political discontent.

The central thesis to the Hudson Bay paper is to leverage tariffs and currency policy in tandem to counterbalance the existing global order. Crucially, he argues that through managed exchange-rate adjustments the exporter’s currency weakens, and they pay the tariff through reduced purchasing power, while U.S. consumers avoid the pain of inflation. Miran points to the 2018–2019 U.S.–China trade war as evidence: U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods (effective rate +17.9 percentage points) were largely neutralized by a 13.7% depreciation of the Chinese renminbi, leaving U.S. import prices only ~4% higher. Throughout, Miran emphasizes tying trade policy to national security. He predicts tariffs will be “deeply intertwined with national security concerns”, effectively using U.S. market access as leverage to make allies and rivals share more of the defense and reserve-currency burden. For example, allies that benefit from the U.S. security umbrella might face tariffs if they don’t open their markets or adjust policies – a form of economic burden-sharing that mirrors Trump’s long-held views on NATO and trade.

A linchpin of Miran’s argument is that the last round of Trump tariffs did not wreak the havoc many predicted. He cites the minimal inflation effect and robust U.S. economy during 2018–2019 as evidence that tariffs need not derail growth if the dollar moves inversely. Indeed, empirical studies found that Chinese exporters lowered prices and the yuan weakened, meaning Chinese firms and the Chinese economy bore a significant portion of the tariff costs. The paper also notes the U.S. treasury revenue from those tariffs, arguing that such income is effectively a transfer from foreign producers to the U.S. government. This is a provocative reframing of tariffs: not just protectionism, but a kind of wealth transfer to fund U.S. public goods (like defense). That framing is politically appealing and somewhat supported by the data – tens of billions were collected from the 2018–19 duties.

However, Miran indicates the theory works if others don’t retaliate - if they do, US consumers will shoulder the cost. The paper flatly states the U.S. is “likelier to win a game of chicken” in tariff showdowns, given its outsized consumer base and deep capital markets. He describes the path to success as “narrow” and warns of substantial market volatility if mismanaged. He suggests phasing policies carefully (e.g. “graduated implementation” of tariffs and coordination with allies) to avoid shock damage. This nuance shows the author is aware that a blunt approach could backfire.

Counterarguments and Alternative Perspectives

Despite its coherent case, Miran’s thesis faces strong counter arguments from many economists and historical precedents. It’s important to scrutinize these opposing views, as they highlight potential weaknesses or oversights in the Hudson Bay analysis.

Trade Deficits as Symptom, Not Theft: critics argue the real issue is U.S. overspending and under-saving—tariffs don’t fix that directly. Miran’s focus on currency misalignment and foreign mercantilism downplays the American side of the equation (fiscal policy, consumer behavior). The U.S. enjoys significant benefits from the dollar’s reserve status (cheap borrowing costs, financial clout) – benefits that his paper casts as net burdens. The truth may be more balanced: the dollar’s role has pros and cons, and “overvaluation” is hard to pin down precisely. If the real issue is that the U.S. consumes more than it produces, tariffs are a roundabout (and potentially costly) way to force adjustment.

Consumer Costs and Inflation: currency offsets help, but some cost increases will still land on U.S. consumers and importers. While the 2018–19 Chinese tariffs had limited inflation impact, they were narrower, communicated in advance, and implemented at a time commodity prices were subdued. A sweeping tariff on all countries could hit everyday consumer goods much harder – from food and apparel to electronics – especially if foreign exchange rates do not adjust enough or quickly.

Retaliation and Global Trade War: History shows retaliation can snowball—this strategy bets on others blinking first. Miran’s strategy hinges on others backing down rather than responding in kind. History gives reason for concern. The infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 provoked widespread retaliation and a collapse in global trade volumes. World trade fell by roughly 66% from 1929 to 1934, an economic catastrophe that worsened the Great Depression. Countries might be so affronted by across-the-board U.S. tariffs that they feel compelled to retaliate despite the economic harm, for domestic political reasons. This could fracture alliances and erode the cooperative institutions (WTO, G7, etc.) that normally resolve disputes. An alternative approach that many experts favor is multilateral negotiation – address issues like Chinese subsidies or European agricultural tariffs through targeted deals or WTO cases, not a blanket tariff war on everyone at once. By lumping friends and rivals together for punishment, the U.S. risks isolating itself and pushing others to coordinate against it, rather than against China (for instance).

In summary, Miran’s thesis is grounded in identifiable problems, but it likely underestimates the adjustment frictions and political backlash of such a radical trade reset. The truth probably lies between the optimistic Hudson Bay scenario and the doomsday trade-war scenario. What’s likely are marginal gains for U.S. industries and a somewhat fairer trading environment, achieved at a significant cost to global stability and efficiency. Essentially, the reality is an uneasy new status quo with higher trade frictions and selective partnerships.

Impacts of the Tariff Regime

Trump’s strategy fuses trade and security, using tariffs not just as economic tools, but geopolitical weapons. The April 2025 trade regime implements the Hudson Bay blueprint to an unprecedented degree. It uses emergency economic powers to rewrite trade relationships overnight, seeking to “rebalance global trade flows” by brute force. The message to trading partners is clear: if you want these tariffs off, come to the table and offer genuine reciprocity (lower your barriers, buy more from the U.S., stop undercutting via currency or subsidies). Until then, the U.S. will tax your exports heavily and continuously – a tax that, in theory, you will bear through currency devaluation or lost volume.

First-order economic impacts include moderately higher U.S. prices on imported goods, reduced import volumes, a likely improvement in the trade balance (by design), and a significant new tax revenue stream. The U.S. economy, being large and diversified, can likely weather these direct effects without recession in the near term – domestic demand and government spending remain strong. However, that’s assuming the situation doesn’t escalate further. The higher-order effects and foreign reactions will determine whether this gambit tips the global economy into a downturn or negotiates a soft landing.

Allies are negotiating, rivals are retaliating, and companies are rethinking where and how they source goods. The broader second-order effects depend on how other nations respond – economically and politically through retaliatory tariffs and trade negotiations along with reordering global supply chains.

Politically, this is causing rifts: pro-globalization factions in those countries are weakened, nationalists there are also gaining voice, arguing they need to be more independent of an unreliable U.S. In NATO and other forums, there’s greater tension – some European leaders hint at closer trade ties with China as a counterweight. However, many allies will likely negotiate instead of escalate. But, domestic political pressure may push escalation over cool headed negotiation.

Developing countries have limited room to respond and are likely to see factory orders cut and job losses. This, in turn, could lead to an increase in global poverty and resultant political instability.

The big bet here is whether the U.S. can absorb blowback better than its rivals and win the game of economic chicken. Shock therapy is underway. Despite calls for caution, the current approach is aggressive, unilateral, and disruptive.

Conclusion

Trump’s trade policy relies on limited, favorable data and simplified models. However clever the scheme is, framing one of the largest tax increases in history so that foreign citizens appear to pay, it can’t be evaluated without real-world stress tests. Now, the global economy is the testbed.

The original framework called for a cautious, coordinated rollout. Instead, we’re getting vague justifications and antagonistic, hostile rhetoric. Allies are confused, citizens are concerned, and the details of the plan remain obfuscated. The market’s reaction reflects that uncertainty. The VIX, a measure of market volatility, spiked 88% the week of the announcement. Investors are left with uncertainty, which gets priced in as risk, and equities sell off.

Worse, the messaging has been glib and detached. Treasury Secretary Bessent recently declared, “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream” - spin with no empathy. Real families live on margins defined by affordability. If this is the cost of rebalancing the global order, the public deserves clarity, not condescension.

This strategy already had a narrow path to success. Poor leadership makes that path even harder to find. Global trade and markets are built on trust. That foundation has been shaken, and the reverberations may last for some time.